Naturalization records can be a critical source when researching your immigrant ancestor. The documents may help you pinpoint their exact time of arrival and identify their place of origin.

Table of Contents

Historical Background

The first naturalization law of the United States dates back to the initial years of the American republic. On 26 March 1790 Congress decreed that all free and white aliens may request naturalization after living in this country for at least two years. Aliens could petition in any court with jurisdiction over their place of residence.1 In 1795 the residency requirement was increased to five years. The law of 25 January 1795 also introduced the two-step process that remained in place until 1952: petitioners needed to first submit a Declaration of Intent, and then three years late, a Petition of Naturalization.2

The most important change to the law—at least for Belgian immigrants—arrived with the naturalization law of 1906.3. The law created the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization to oversee all naturalization proceedings.4 It introduced standardized forms for the Declaration of Intent and Petition of Naturalization, required a certificate of arrival, as well as sworn statements of two witnesses. From now on, courts also needed to send duplicate copies of all documents to the federal bureau. Local and regional judges could still bestow citizenship, but in practice, this role fell more and more to the federal courts. Some local benches however continued to process naturalization until well in the nineteen eighties.

In other words, before 29 June 1906, naturalization was a judicial procedure that followed the law but was not regulated by the federal government. Any municipal, county, state, or federal court could establish its own process with its own unique forms. Fraud was not uncommon. Immigrants primarily pursued citizenship in order to buy land, increase their employment opportunities, or participate in local and national elections. Political parties recruited immigrants for naturalization during the months, weeks, and even the day before an important election. It is precisely to combat such schemes that Congress decided to act in 1906.

After 29 June 1906 naturalization proceedings could still take place in local courts, but each court needed to follow the same process and use the same forms, as well as send duplicate copies of each document to the federal government. In practice, the role of naturalization fell more and more to the federal courts. However, some local benches continued to bestow citizenship until the late eighties of the last century.

All this has important consequences for the genealogist, both as to where naturalization files are stored, and as to what information one may expect to find in the records.

What genealogical information is contained in naturalization records?

The family historian searches for three naturalization records: (1) the Declaration of Intent, also called First Papers; (2) the Petition for Naturalization, also called Final or Second Papers; and (3) the Certificate of Citizenship.

Before July 1906 these documents varied widely in both form and content. Some courts used separate forms, often bound later into volumes. Others wrote the data into large, pre-printed registers. And yet other benches simply made a note about the proceedings in their docket. Information about the immigrant’s origins was often very concise and not always scrutinized for accuracy.

Naturalization documents created after July 1906 all look the same and contain identical information. From now on the declaration and petition usually contain the exact place and date of birth of the alien and—when applicable—his wife and children. The forms also list the exact time and place of the immigrant’s arrival in the United States. From 1929 onwards, the Declaration of Intent includes a photo of the applicant.

Declaration of Intent

Before July 1906

- Name

- Country of birth/previous nationality

- Date of request

- Age (sometimes)

- Date and place of arrival in the US (sometimes)

- Date of Declaration of Intent (sometimes)

After July 1906

- Name

- Age

- Physical description

- Date and place of residence

- Date and place of arrival in the US

- Name of spouse and her place of birth

- Date of request

- Photo (1929 onwards]

Petition for Naturalization

Before July 1906

- Name

- Country of birth/previous nationality

- Date of request

- Age (sometimes)

- Date and place of arrival in the US (sometimes)

- Date of Declaration of Intent (sometimes)

After July 1906

- Name

- Current residence

- Ooccupation

- Date and place of birth

- Date and place of arrival in the US

- Date of declaration of intent

- Name of spouse, her place and date of birth, her current residence

- Name of minor children, their place and date of birth, their current residences

- Name of the government of the immigrant’s place of origin

- Length of residency in current state

- Name of witnesses, their occupation and residence

- Date of request

Certificate of Naturalization

Before July 1906

- Date of naturalization

- Name

- Country of birth/previous nationality

- Date of Declaration of Intent

- Name of witnesses

After July 1906

- Date of naturalization

- Name

- Age

- Country of birth/previous nationality

- Physical descrption

- Name, age, and residency of spouse and minor children

A few examples to illustrate:

François Joseph Lardinois, originally from Walhain-Saint Paul in Walloon Brabant, declared his intent to become an American citizen on 8 May 1854 and received his citizenship on 29 January 1889 at the Brown County Circuit Court in Wisconsin.5

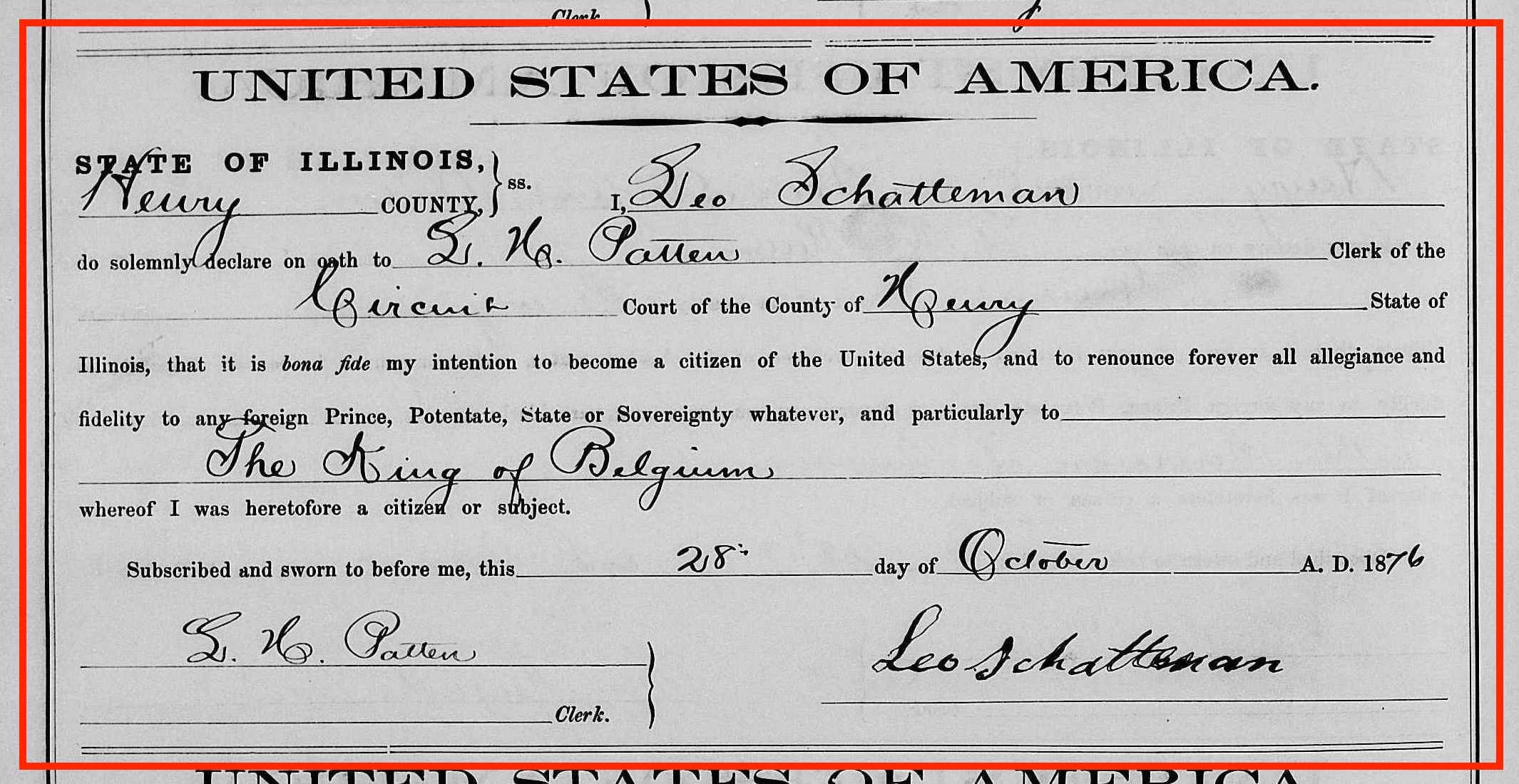

Leo Schatteman, who hailed from Lotenhulle in West Flanders, became an American citizen on 12 April 1879 before the Henry County Court in Illinois. His Declaration of Intent was filed on 28 October 1876. Neither document reveal a whole lot more about Leo.10

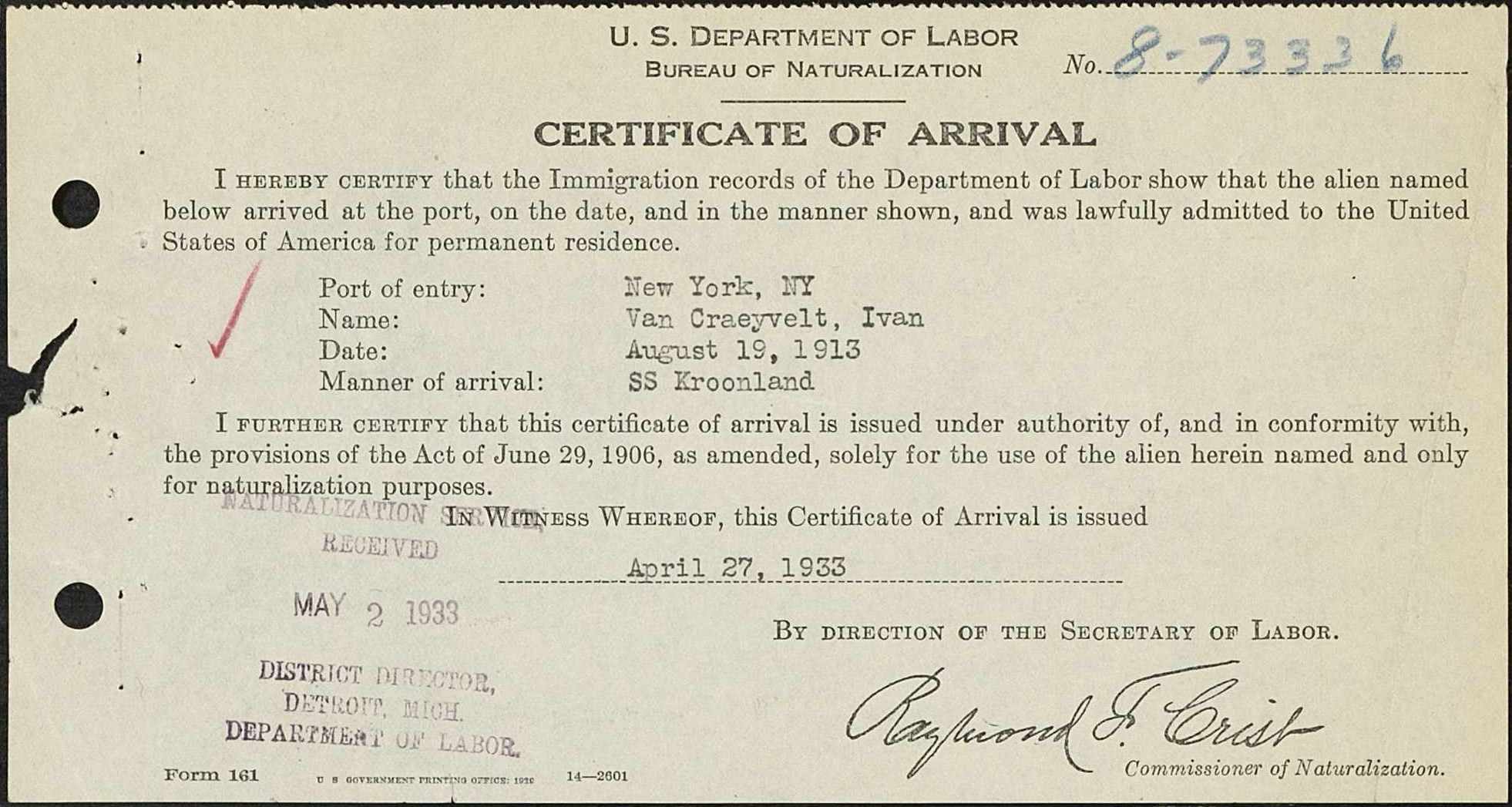

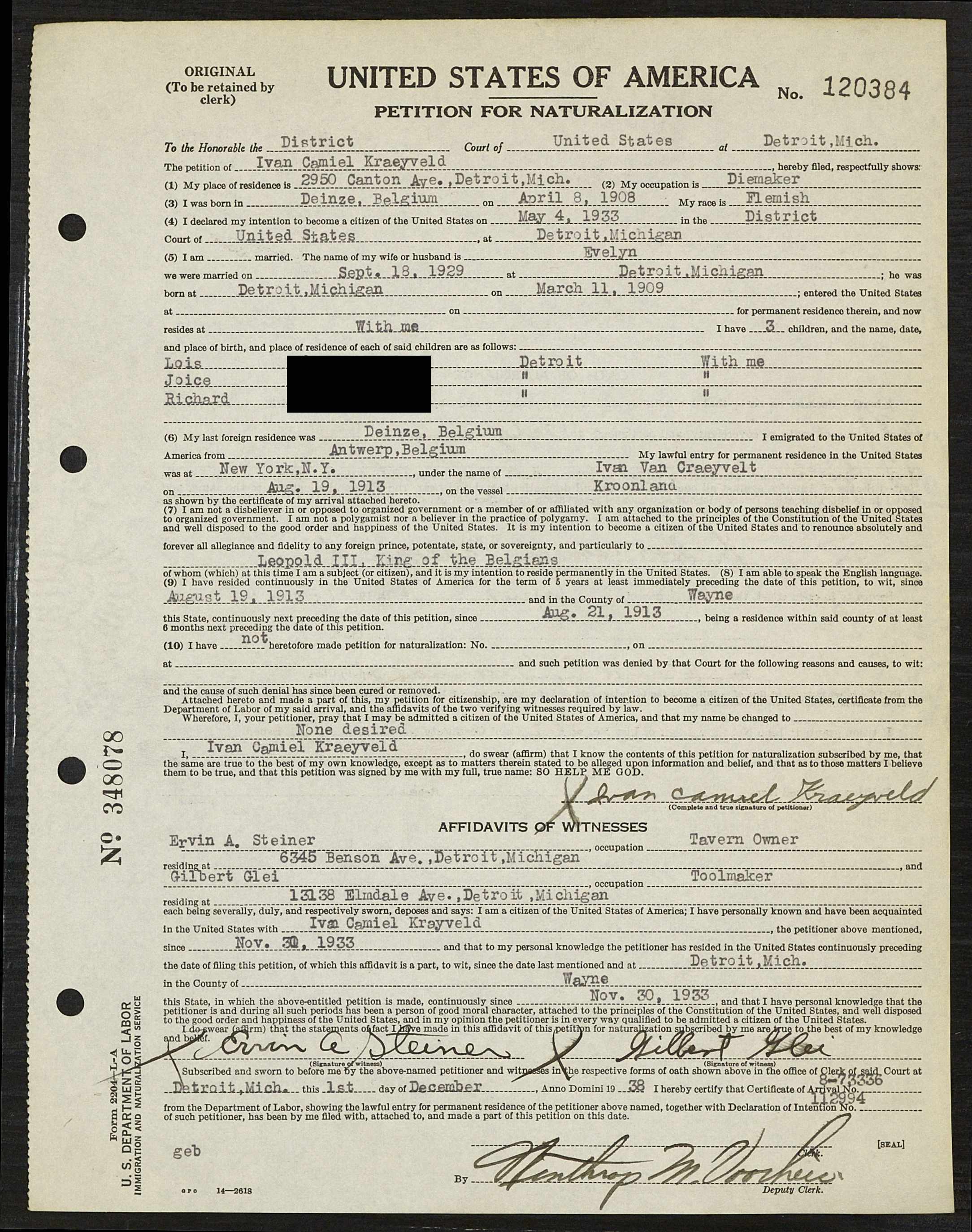

Ivan Camiel Kraeyveld from Deinze in East Flanders pledged allegiance to the United States on 6 April 1939 in Detroit. His Declaration of Intent is dated 30 November 1933. The document contains his photograph, his exact place and date of birth (Deynac [i.e., Deinze], 8 April 1908), the first name of his wife, and her place of birth (Evelyn, born in Detroit), his physical description (blue eyes, brown hair, 5 feet 7 inches, 140 lbs.), his current residence (Detroit), and his arrival in the United States (arrived 19 August 1913 in New York aboard the SS Kroonland). A certificate of arrival, dated 27 April 1933, confirms the latter. Ivan submitted his petition on 1 December 1938. The petition includes the names of his children and their place and date of birth.[/efn_note]

Where Are Naturalization Records Preserved?

Unfortunately, there is no one-stop-shopping! Before 1906 the possibilities are multiple: local courthouses, local and regional archives, genealogical or historical societies, university archives, and more. Only those files that were created by Federal District Courts found their way to the National Archives. Some duplicates and the unique certificate—when this was provided—survive in family archives. Once in a while, genealogists also encounter naturalization records in other court files, homestead applications, or passport requests.

After 1906, three copies were made of both the declaration and petition. The court where the proceedings were held kept the original documents. As before, these originals can still be found at a multitude of courts, archives, and societies. Duplicates were sent to the Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization, and over time transferred to the National Archives. The applicant received the triplicate copy of the Declaration of Intent, whereas the third copy of the Petition for Naturalization landed on the desk of the local federal immigration examinor.

Immigrants usually proceeded to the nearest courthouse to request naturalization. Genealogists should therefore start the search in the immigrant’s county of residence. Most often, the immigrant started and ended the proceedings in the same court, but there are exceptions. The researcher should also consider the possibility that his or her ancestor did not complete the entire process. During the nineteenth century some states only required a Declaration of Intent in order to purchase land, open a business, or vote in the upcoming election. Some immigrants did not bother with the final step.

How Can Genealogists Consult Naturalization Records?

Online

Many, though not all, naturalization records have been microfilmed and made available in digital format.

FamilySearch and Ancestry both contain multiple indexes which are often linked to the digital images of original records. Some collections however have not yet been indexed and the researcher needs to browse the individual images. A single, all-encompassing index does not exist.

At FamilySearch a great starting point is the Wiki page “United States Naturalization and Citizenship Online Genealogy Records.” FamilySearchWiki pages for each state (and some counties) also discuss naturalization records. Another approach is to search the FamilySearch Catalog for the county of interest, and the subject “Naturalization and citizenship.”

Ancestry has a portal for all United States naturalization documents: U.S. Naturalization Records. A search here can result in an index card containing naturalization data or lead you to the original record. A search for “born in Belgium,” at the time of writing resulted in 66,069 hits. The page also contains links to 60+ regional indexes, some of which do not require a subscription to the site. U.S., Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project), for example, is a free resource. Be aware however that, regardless of its name, the database contains information for a limited number of states (Alaska, California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Montana, New England, New York, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, and Washington). A search here results in an image of a Soundex index card that provides the immigrant’s name, date of naturalization, and name of the court. As such it provides the researcher only with a hint as to where the original documents may reside. A search “born in Belgium” at the time of writing resulted in 14,235 hits.

Bricks-and-Mortar

Naturalization documents that have not yet been digitized can be requested from the court, archive, or organization where they are stored. In some cases, this requires a research trip to the repository. For files that pre-date the law of 1906, genealogists may need to contact the offices of the County Clerk, the State Archive, Library, or Historical Society. Some counties, such as Cook County, Illinois, have an online genealogy index. The Michigan State Archives preserve the files for several counties in the state. But naturalization documents from the Detroit Recorders Court in Michigan are part of the the Burton Historical Collection at the Detroit Public Library. In Illinois, documents can be found at one of the Illinois Regional Archives Depositories. For Minnesota and Wisconsin ancestors, researchers can contact the respective State Historical Society. However, if you are looking for the documents of ancestors who settled in the Brown, Door, or Kewaunee Counties of Wisconsin, they need to direct their query to the archives of the University of Wisconsin in Green Bay.

Federal documentation records (before and after 1906) are kept at the regional facilities of the National Archives. For the Midwest, where many Belgians settled, this is the National Archives at Chicago.

USCIS Genealogy Program

For a fee, researchers can also request federal naturalization files through the Genealogy Program of the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). Unless you have the exact number of the file needed, this route first requires a general index search. Subsequently, you can order digital copies of each file found. At the time of this writing, both the index search and copies of each file are provided for $65.

USCIS files may contain one or more of the following records:

Certificate Files (C-Files): 27 September 1906-March 1956

C-Files are naturalization files for immigrants who requested naturalization after the 29 June 1906 law, or whose earlier naturalization was in any way examined or reviewed after June 1906 (e.g., in the case of repatriation, or when the immigrant, his wife or one of the children, needed proof of citizenship). At the very least, C-Files contain the duplicate copy of the Declaration, Petition, and final Certificate, but C-Files can also include additional supporting documentation. The more complicated the case, the thicker the file. Usually the C-File is the only place where a genealogist can find the Certificate of Citizenship (the only other copy was given to the immigrant and has often been lost). Note: C-Files may also include consolidated A-Files, Visa Files or AR-2 Forms (see below).18

Visa Files: July 1924-March 1944

In 1924 a new immigration law required each arriving immigrant and foreign visitor to the United States to obtain a visa before arriving. The tourist or immigrant requested this visa at the American embassy or consulate in his or her country of residence, and then submitted the paperwork at the port of arrival. Until the end of March 1944, visas were the official arrival record for each immigrant. The Immigration and Naturalization Service in Washington, D.C. saved the records, and they are now part of the Visa Files at USCIS. The files usually contain the application form, copies of pertinent vital records, a medical certificate, and an affidavit of good moral conduct. Note: from April 1944, Visa Files were consolidated to A-Files (see below). Visa Files of immigrants who naturalized between April 1, 1944 and the end of March 1956 were combined with the C-File (see above).19

Registry Files: March 1929-March 1944

The Immigration and Naturalization Service created registry files for those naturalization applicants who could not present a certificate of arrival (required since July 1906). In 1929 a law enacted by Congress allowed such immigrants to demonstrate to the Commissioner General of Immigration with other documents that he or she is be eligible to obtain American citizenship.21. Registry files usually pertain to immigrants who arrived prior to July 1924. The files typically include a detailed account of the immigrant’s trip to America and their subsequent stay in the United States, complete with letters, witness statements, and a photograph.22

Alien Registration Forms (AR-2s): August 1940-March 1944

After Pearl Harbor and the outbreak of World War II the United States mandated every alien, older than fourteen, to register with the government.24. Belgian-Americans who had not yet naturalized also fell into this category. Between August 1940 and the end of March 1944 5,665,983 foreigners registered with the government. They completed an Alien Registration (AR-2) Form and received a unique A-Number. Note: some AR-2 Forms were later consolidated with a C- or A-File.

Alien Files (A-Files): Since April 1944

In April 1944 the Immigration and Naturalization Service decided to consolidate all the immigration and naturalization records pertaining to an immigrant into one A-File upon the immigrant’s naturalization. From that date until March 31, 1956, all records were placed in the immigrant’s C-file. Beginning April 1, 1956, all documents went into the A-file.26

The A-Number, assigned to each non-American-citizen since 1940 (see AR-2 Forms above) provided the basis for this dossier.

If the immigrant naturalized before 1 April 1956, the Immigration and Naturalization Service transferred the closed A-File to a C-File (see above). USCIS still creates an A-File for each new immigrant.

The content of A-Files varies. Some folders contain three one-page documents, others include three hundred pages. At the very least, an A-File contains a copy of the AR-2 Form and a card with the immigrant’s subsequent places of residence. Files for immigrants who naturalized after March 1956 also include all naturalization documents (Declaration of Intent, etc.).

In 2009 USCIS started transferring the A-Files for immigrants born more than one hundred years to the National Archives, a process which has not yet been completed. A very incomplete index to the transferred files is available at Ancestry. The National Archives catalog provides much better access. Genealogists can search by name or by A-Number. Copies of the files can be requested via email.

Other Documents with Naturalization Information

Finally, several other records contain information about Belgian Americans’ naturalization status.

Census

The 1890–1930 census records include the answers to questions about every American citizenship status. Abbreviations used include AL (alien), NA (naturalized), NR (not reported), PA (first papers filed), and IN (Declaration of Intention filed).

| 189029 | How many years has the person been in the United States? Is the person naturalized? Has the person taken naturalization papers out? |

| 1900 | What year did the person immigrate to the United States? How many years has the person been in the United States? Is the person naturalized? |

| 1910 | Year of immigration to the United States Is the person naturalized or an alien? |

| 1920 | Year of immigration to the United States Is the person naturalized or alien? If naturalized, what was the year of naturalization? |

| 1930 | Year of immigration to the United States Is the person naturalized or an alien? |

Passenger Lists

Passenger lists can also naturalization clues. After 1906, examiners of the Immigration and Naturalization Service checked the legal arrival of each immigrant. Starting in 1926, the agents made notations on the passenger lists so that subsequent officers would know whether a particular immigrant’s arrival record had already been verified for naturalization. For example, the numbers 8 73336 next to Ivan Van Craeyvelt’s name on the August 1913 manifest of the SS Kroonland refers to the district that processed his application (8) and the number of his Certificate of Arrival (73336).

Passport Applications

First generation Belgian-Americans need to provide proof of citizenship when they apply for a United States passport, therefore passport applications include the date and court of naturalization.

Military Draft Registration Cards

In 1917 and 1918, thousands of Belgians in America registered for the military draft and were asked about their citizenship status. John Dooms, from Desselgem in East Flanders, registered for the draft on 5 June 1917 in Omaha, Nebraska. His Registration Card reveals that he was a declarant, i.e., had filed his first papers.

Selective List of Online Sources

Ancestry ($): http://www.ancestry.com

- U.S. Index to Alien Case Files, 1940-2003: https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/2540918

- U.S. Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project): http://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1629/

- U.S. Naturalization Records (Portal): http://www.ancestry.com/search/categories/us_naturalization/

Cook County, Illinois (Chicago): http://www.cookcountyclerkofcourt.org/NR/

FamilySearch: http://www.familysearch.org/

- Catalog: http://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog

- United States Index to Alien Case Files, 1940-2003: http://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/2540918

- United States Naturalization Laws:https://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/United_States_Naturalization_Laws

- Wiki United States Naturalization and Citizenship: http://www.familysearch.org/wiki/en/United_States_Naturalization_and_Citizenship

GermanRoots: http://www.germanroots.com/naturalization.html

Illinois Regional Archives Depositories: http://www.cyberdriveillinois.com/departments/archives/IRAD/

Michigan State Archives: http://michiganology.org/naturalization/

Minnesota Historical Society: http://libguides.mnhs.org/naturalization

National Archives: http://www.archives.gov/

- Catalog: http://www.archives.gov/research/catalog

- Naturalization: http://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/naturalization

- Regional Branches: http://www.archives.gov/locations

University of Wisconsin—Green Bay: http://www.uwgb.edu/archives/collections-more/genealogy-and-local-history/

United States Citizenship and Immigration Services: http://www.uscis.gov

- Genealogy Program: http://www.uscis.gov/records/genealogy

- History Office and Library: http://www.uscis.gov/about-us/our-history/history-office-and-library

Wisconsin Historical Society: http://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Article/CS74

For More Information

- Cohn, D’Vera. “How U.S. Immigration Laws and Rules Have Changed Through History,” Fact Tank (blog), 30 September 2015 (https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/09/30/how-u-s-immigration-laws-and-rules-have-changed-through-history/).

- Daniels, Roger. Guarding the Golden Door: American Immigration Policy and Immigrants Since 1882. New York: Hill & Wang, 2004.

- Newman, John J. American Naturalization Records 1790-1990: What They Are and How to Use Them. Bountiful, Utah: Heritage Quest, 1998.

- Kettner, James H. The Development of American Citizenship, 1608-1870. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1978.

- Parker, Kunal M. Making Foreigners: Immigration and Citizenship Law in America, 1600-2000. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

- Schaefer, Christina K. Guide to Naturalization Records of the United States. Baltimore: Genealogical Pub. Co., 1997.

- Smith, Marian L. “Certificates of Arrival, the “Morton Allan Directory,” and the Accuracy of Arrival Information Found in Naturalization Records.” Avotaynu: The International Review of Jewish Genealogy 14, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 1-10. https://inrecordsfortnightly.squarespace.com/s/Wladislaw-Newer.pdf.

- Smith, Marian L. “A Guide to Interpreting Passenger List Annotations.” https://www.jewishgen.org/infofiles/manifests/. Last revised 29 September 2002.

- Smith, Marian L., and Claire Prechtel-Kluskens. “Research Guide to Selected Bureau of Naturalization Case and Correspondence Files, 1906-1946.” Washington, DC: National Archives and Records Administration, 2013. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/naturalization/naturalization-files.pdf.

- Szucs, Loretto Dennis. They Became Americans: Finding Naturalization Records and Ethnic Origins. Salt Lake City, Utah: Ancestry, 1998.

- U.S. National Archives & Records Administration. “Major United States Laws Relating to Immigration and Naturalization: 1790–2005.” National Archives (website). Revised November 2014. https://www.archives.gov/files/research/naturalization/420-major-immigration-laws.pdf.

- Zolberg, Aristide. A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2006.

Cite This Post

Kristine Smets, “Finding Your Belgian Ancestor In Naturalization Records,” The Belgian American (https://thebelgianamerican.com : accessed [date]), posted 9 May 2020.

- US Congress, Statutes at Large, vol. 1, 103-104, “An Act to Establish an Uniform Rule of Naturalization”; digital image, Library of Congress Law Library (https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large), > 1st Congress > Session 2 > Chapter 3. URLs were last viewed on 9 April 2021.

- US Congress, Statutes at Large, vol. 1, 414-415, “An Act to Establish an Uniform Rule of Naturalization; and to Repeal the Act Heretofore Passed on That Subject”; digital image, Library of Congress Law Library (https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large), > 3rd Congress > Session 2 > Chapter 20.

- US Congress, Statutes at Large, vol. 34, 596-607, “An Act to Establish a Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization, and to Provide for a Uniform Rule for the Naturalization of Aliens Throughout the United States;” digital image, Library of Congress Law Library (https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large), > 59th Congress > Session 1 > Chapter 3592.

- For a timeline of the federal immigration and naturalization service, see ” Organizational Timeline,” U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (https://www.uscis.gov/about-us/our-history/organizational-timeline).

- For his birth, see Walhain-Saint-Paul, Brabant Méridional, Registre des naissances pour l’an 1825, no. 49, François Joseph Lardinois; digital Image, “Belgium, Brabant, Civil Registration, 1582-1914,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9YMC-FPT).

- Brown County Circuit Court, Illinois, Declaration of Intention, François J. Lardinois (1889); digital image, “Wisconsin, County Naturalization Records, 1807-1992,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:ZZLT-8Q2M).

- Brown County Circuit Court, Illinois, Petition, François Jos. Lardinois (1854); digital Image, “Wisconsin, County Naturalization Records, 1807-1992,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:ZZ43-WXPZ), Francis J. Sardinois, 1889.

- United States of America, Certificate of Naturalization, Francis Lardinois (1889); personally held by John Smits, Sun City, Florida.

- Francis Joseph Lardinois (1825-1905); personally held by John Smits, Sun City, Florida.

- For his birth in Lotenhulle, see Lotenhulle, Oost Vlaanderen, Register van Geboorten voor 1823, no. 67, Leonardus Schatteman; digital image, “Belgique, Flandre-Orientale, registres d’état civil, 1541-1914,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GG89-9BT4).

- Henry County Court, Illinois, Naturalization Records, vol. C, p. 182, Leo Schatteman; digital image, “Illinois, County Naturalization Records, 1800-1998,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:7VC6-2K6Z).

- Henry County Court, Illinois, Final Naturalization Records, vol. A, p. 155, Leo Schatteman; digital image, “Illinois, County Naturalization Records, 1800-1998,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:7VCH-QSN2).

- District Court of the United States, Detroit, Michigan, Declaration of Intention no. 112994, Ivan Camiel Kraeyveld (1933).

- U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Naturalization, Certificate of Arrival no. 8-73336, Ivan Camiel Kraeyveld (1933).

- District Court of the United States, Detroit, Michigan, Petition for Naturalization no. 120384, Ivan Camiel Kraeyveld (1938).

- District Court of the United States, Detroit, Michigan, Petition for Naturalization no. 120384, Ivan Camiel Kraeyveld (1938).

- U.S., Naturalization Record Indexes, 1791-1992 (Indexed in World Archives Project),” Ancestry (https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1629/), entry for François Lardinois; citing National Archives and Records Administration, Soundex Index to Naturalization Petitions for the United States District and Circuit Courts, Northern District of Illinois and Immigration and Naturalization Service District 9, 1840-1950; NARA microfilm M1285, roll 115.

- “Certificate Files, September 27, 1906 – March 31, 1956,” U.S. Immigration and Naturalization ServiceGenealogy Program (https://www.uscis.gov/records/genealogy), > Genealogy > Historical Record Series > Certificate Files, September 27, 1906 – March 31, 1956.

- “Visa Files, July 1, 1924 – March 31, 1944,” U.S. Immigration and Naturalization ServiceGenealogy Program (https://www.uscis.gov/records/genealogy), > Genealogy > Historical Record Series > Visa Files, July 1, 1924 – March 31, 1944.

- American Consular Service, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, Application for Immigration Visa (Quota), Adolph Hullman (1926).

- US Congress, Statutes at Large, vol. 45, 1512-1517, “An Act to Supplement the Naturalization Laws, and for Other Purposes”; digital image, Library of Congress Law Library (https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large), > 70th Congress > Session 2 > Chapter 536.

- “Registry Files, March 2, 1929 – March 31, 1944,” U.S. Immigration and Naturalization ServiceGenealogy Program (https://www.uscis.gov/records/genealogy), > Genealogy > Historical Record Series > Registry Files, March 2, 1929 – March 31, 1944.

- U.S. Department of Labor, Immigration Service, Application for Registry of an Alien under an Act of Congress Approved March 2, 1929, Klemens Akalski (1930).

- US Congress, Statutes at Large, vol. 54, 670-671, “An Act to Prohibit Certain Subversive Activities; to Amend Certain Provisions of Law With Respect totThe Admission and Deportation of Aliens; Tt Require the Fingerprinting and Registration of Aliens; and for Other Purposes (Smith Act)”; digital image, Library of Congress Law Library (https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large), > 76th Congress > Session 3rd > Chapter 439.

- U.S. Department of Justice, Immigration and Naturalization Service, Alien Registration Form, Margaretha Schimmel (1940).

- Note: If the immigrant naturalized before the 1944 date all his records would NOT be consolidated.

- 1900 U.S. census, Kewaunee, Wisconsin, population schedule, Red River Township, ED 62, sheet 1B, fol. 155vo, dwelling 14, family 14, Frank Lardinois, head; digital image, “United States Census, 1900,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MMVH-3MX); citing National Archives microfilm publication T623, roll 1794.

- 1930 U.S. census, Wayne, Michigan, population schedule, Detroit, ED 820, sheet 115A, fol. 220ro, dwelling 560, family 2, Ivan Kraeyveld, head; digital image, “United States Census, 1930,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X7SL-JNY); citing National Archives microfilm publication T626, roll 1065.

- Most of the 1890 census was destroyed during a fire in 1921. See, “Availability of the 1890 Census,” United States Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/history/www/genealogy/decennial_census_records/availability_of_1890_census.html).

- “Index of Questions,” United States Census Bureau (https://www.census.gov/history/www/through_the_decades/index_of_questions/).

“New York Passenger Arrival Lists (Ellis Island), 1892-1924,” FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:JNBF-V6R), manifest SS Kroonland, Antwerp, Belgium, to New York, New York, arriving 19 August 1913, fol. 22 (stamped), line 30, Ivan Van Craeyvelt; citing Passenger and Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York, New York, 1897-1957. Microfilm Publication T715, roll 2156.- United States, Department of State, Passport Application for Naturalized Citizen, Gustave De Cock (1923); digital Image, “United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVJG-PY2J), Gustave Decock, 1923; citing Passport Application, Maryland, United States, source certificate #267553, Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925, 2220, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.).

- “United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:29JJ-1B4), entry for John Dooms; citing NARA microfilm publication M1509

Kristine: thank you for your explanation of the naturalization process and information, another of your excellent and well-researched articles!!