This weekend, as many of us celebrate Mother’s Day, might be the perfect time to delve into your maternal roots. Who was your mother’s mother? Who was her mother, and her mother’s mother, and so on? Not as easy perhaps as tracing your paternal line, but researching the many mothers who contributed to your existence can have its own rewards.

Genealogists with Belgian roots have an advantage when researching their female ancestors: women in Belgium did not (and still do not) forsake their maiden name upon marriage.2For example, my paternal grandmother, Maria Willemse, remained Maria Willemse when she married my grandfather Armand Smets.3The reason lies not just in tradition, but also in the law. Surnames in Belgium were officially registered in 1795 during the French occupation, and since then, family names can only be altered under specific limited circumstances. A change of surname still requires approval by the King of Belgium. As a result of this legal impediment to changing one’s family name, Belgian genealogical records, such as birth, marriage, and death records, always include women’s maiden names.

The abundance of detailed civil registration records in Belgium also makes tracing your Belgian ancestors a fairly simple process. Until at least 1795, the year civil registration was introduced in the Southern Netherlands, each vital record usually contains enough clues to locate the earlier ancestor.4Parish records are a bit harder to analyze but it is not uncommon for Belgian genealogists to trace their roots back to the seventeenth or even sixteenth centuries.

If your maternal line extends back to Belgium (Wallonia, Brussels, or Flanders), you now also have the unique opportunity to participate in MamaMito, a Flemish citizen science project that focuses on matrilinear lines and mitochondrial DNA.5 Participants in the project are eligible to be selected for a free mtDNA analysis.

MamaMito was launched on March 1, 2020, by KU Leuven (Catholic University of Leuven) and Histories vzw, the Flemish cultural organization for genealogy, local history, and cultural heritage. Head researcher is Dr. Maarten Larmuseau, an international authority in genetic genealogy, and professor at the Department of Human Genetics at KU Leuven.6

A few years ago, Dr. Larmuseau’s research into historic cuckoldry rates [koekoeksgraad] in Belgium made the science pages of the New York Times. Using Belgium’s detailed birth records, Larmuseau and his colleagues reconstructed large family genealogies reaching back four centuries and sequenced the Y chromosomes of living male descendants. What they found was a surprising rate of less than one percent, much smaller than the commonly assumed rate of misattributed parentage.7

With MamaMito Larmuseau and his team are now turning their attention to our matrilineal lines, lineages commonly ignored by genealogists. One of the project’s goals is to encourage research into maternal ancestors by providing free genealogical education and an online forum for sharing results. Participants who join the project can contribute their data until the end of August 2020.

But the project also has a scientific component. At the end of August, MamaMito will select 200 couples of distant cousins and invite them to test their mitochondrial DNA as part of a scientific study.8 By analyzing the anonymized mtDNA results and corresponding family trees, the researchers hope to answer some of the following questions: How often does mtDNA change? Is there a discrepancy between traditional and genetic family trees? Is there a distinct Flemish variant of mtDNA? They expect to publish their findings in 2021.

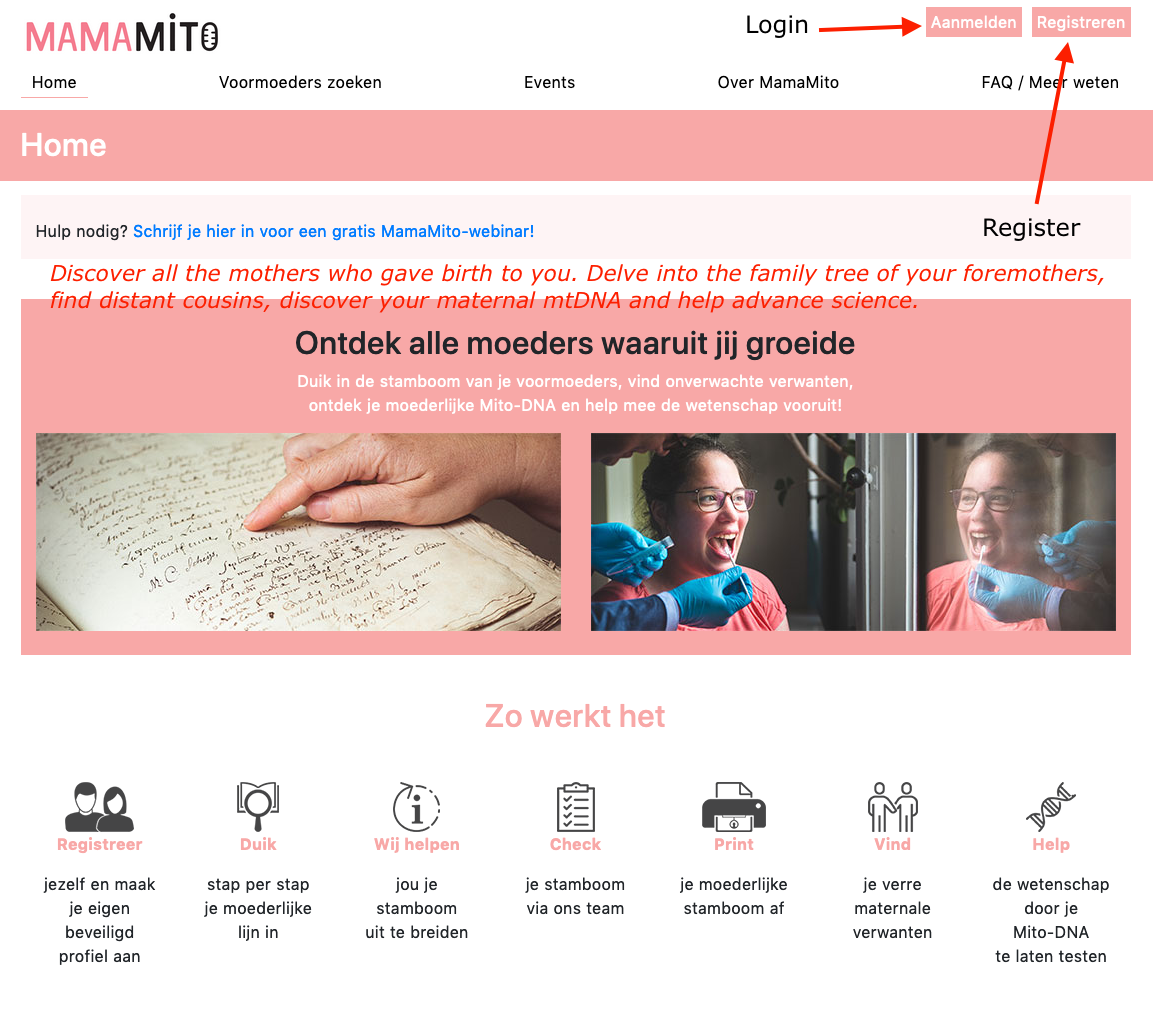

Mamamito is not limited to Belgian citizens. You too can join the project. The website has a Dutch interface only, but is not too difficult to navigate.9 Google translate or FamilySearch’s Dutch Genealogical Word List can help if you are stumped by some of the Dutch vocabulary. What follows are a few screenshots and tips to help you get started.10

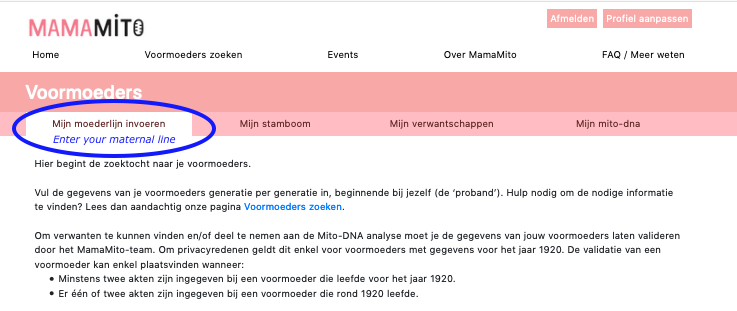

First log on to https://mamamito.be/ and register as a new participant.

Once you are registered and logged in, start entering your data by selecting the Mijn moederlijn invoeren tab [Enter your maternal line].

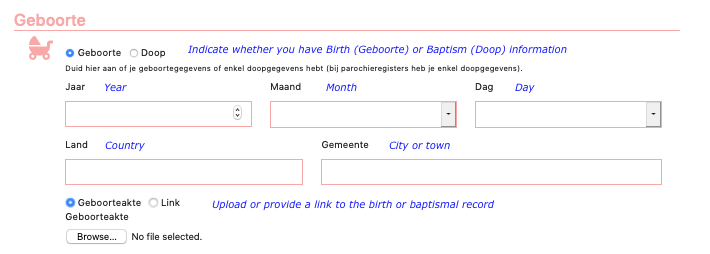

Starting with yourself, enter the following data for each of your maternal ancestors: name [naam], birth [geboorte] or baptism [doop], marriage [huwelijk], death [overlijden] or burial [begrafenis]. For each event older than 100 years you will need to upload (or provide a link to) a source document, such as a vital record, that can support your information.

Enter your ancestor’s name, first name, and – if applicable – her nickname.

Enter her birth or baptismal information.

Enter marriage information.

Enter death or burial information.

A specialized team of experts will validate your data, but, in order to protect your privacy, only for those ancestors who lived more than 100 years ago.11

At any time, you can view and print your maternal line by going to the Mijn stamboom [My family tree] tab.

You can download and print your maternal line in two unique lay-outs. One entitled Een Museum van Moeders [A Museum of Mothers] starts with you and works its way backwards.

The second one, called Alle Moeders Waaruit Ik Groeide [All The Mothers From Which I Grew], presents your maternal line starting with your earliest ancestor.

Soon you will also be able to download your data to a gedcom file from this same page, so that you can upload it to genealogical software of your own choice.12

You can view your distant cousins by selecting the Mijn verwantschappen [My relatives] tab. But keep in mind that your maternal line must be validated before relatives can be found, and, due to privacy reasons, the webapp will only reveal relationships that date back more than 100 years.

Finally, if you would like to be eligible for the free mtDNA test, you must send an email to the researchers at dna@historiesvzw.be. They will send their DNA-kits across the globe, so US residents are more than welcome to participate. I am confident you are free to write the team in English.

Participating in MamaMito inspired me to delve into some of my neglected ancestral lines. I was able to reach the eighteenth century and my 5th great-grandmother within a few days of research. I hope to make it to the 1700s before the project ends so that I can honor the contributions of my foremothers to the world.

Cite this post

Kristine Smets, “Research Your Maternal Line with MamaMito,” The Belgian American, (https://thebelgianamerican.com : accessed [date]), posted 9 May 2020.

- All MamaMito images provided by Dr. Maarten Larmuseau and used with permission.

- See “Giving a Name,” Foreign Affairs, Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation (https://diplomatie.belgium.be/en/services/services_abroad/registry/giving_a_name : accessed 7 May 2020), scroll down to “Will marriage affect my surname?” Also, “Veranderen van Familienaam,” Vlaanderen.be (https://www.vlaanderen.be/veranderen-van-familienaam : accessed 7 May 2020). Also, “Verandering Familienaam,” Federale Overheidsdienst Justitie (https://justitie.belgium.be/nl/themas_en_dossiers/personen_en_gezinnen/naamsverandering/verandering_familienaam : accessed 7 May 2020).

- Letters address to a married couple and married woman in Belgium use a hyphenated formula. E.g. De Heer en Mevrouw Smets-Willemse, and Mevrouw Maria Smets-Willemse.

- For more information see my earlier blog post “About Belgian Vital Records.”

- Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is located in each cell of our body outside the cell’s nucleus. A mother passes her mtDNA to all of her children, but a male does not pass his mtDNA to his children. Because of this unique inheritance pattern, and the relatively low rate of mtDNA mutations, the same mtDNA footprint is passed down for many generations, and can be used to validate a matrilineal ancestral line. See Blaine T. Bettinger and Debbie Parker Wayne, Genetic Genealogy in Practice (Arlington, VA: National Genealogical Society, 2016), p. 46-48.

- For a bibliography of his many scientific publications, see https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Maarten_Larmuseau/2#research-items.

- Carl Zimmer, “Fathered by the Mailman? It’s Mostly an Urban Legend,” New York Times 8 April 2016, Web edition (https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/12/science/extra-marital-paternity-less-common-than-assumed-scientists-find.html : viewed 7 May 2020); citing section A, p. 1. See also M.H.D. Larmuseau et al., Low historical rates of cuckoldry in a Western European human population traced by Y-chromosome and genealogical data,” Proceedings of the Royal Society, B Biological Sciences 280:1772 (7 December 2013); online archives, The Royal Society Publishing (https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2400 : accessed 7 May 2020). Dr. Larmuseau also regularly publishes columns in the Vlaamse Stam, the flagship journal of the Flemish Genealogical Society. His latest column discussed much higher cuckoldry rate among poor urban families. See “Meer Koekoekskinderen Geboren bij Arme Stadsgezinnen in de 19de Eeuw: De Finale Resultaten van De Gen-iale Stamboom,” [More Cuckold Children Born Among Poor Urban Families in the 19th Century: The Final Results of the Gen-ial Family Tree] Vlaamse Stam 56:1 (2020), p. 6-9.

- The lucky 400 will receive their test results about six months later in a strictly private manner.

- The project is sponsored by the Flemish government.

- Screenshots created by author and posted with permission of Dr. Larmuseau.

- MamaMito’s privacy notice meets or exceeds the strict 2016 European standards of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

- .This functionality is promised for 15 May 2020.

- Photograph posted with permission from living family members.

What a wonderful and fascinating post! Thank you, Kristine.