Of the dead (say) nothing but good

The custom of distributing death memorial cards during Roman-Catholic funeral services dates back to the seventeenth century. At first they were handwritten, but during the early nineteenth century printed cards became the norm. Initially reserved for bishops, priests, and other dignitaries, the prayer card tradition spread to the upper and middle classes, and the development of inexpensive printing techniques made them more affordable to all members of society by the early twentieth century. 1

Though not as rich as mourning letters, memorial cards contain brief genealogical information with many clues for the savvy genealogist. At the very least they provide the place and date of birth and death for the deceased. Cards also customarily include the name of spouse(s), both deceased and living. Cards for young children mention the parents.

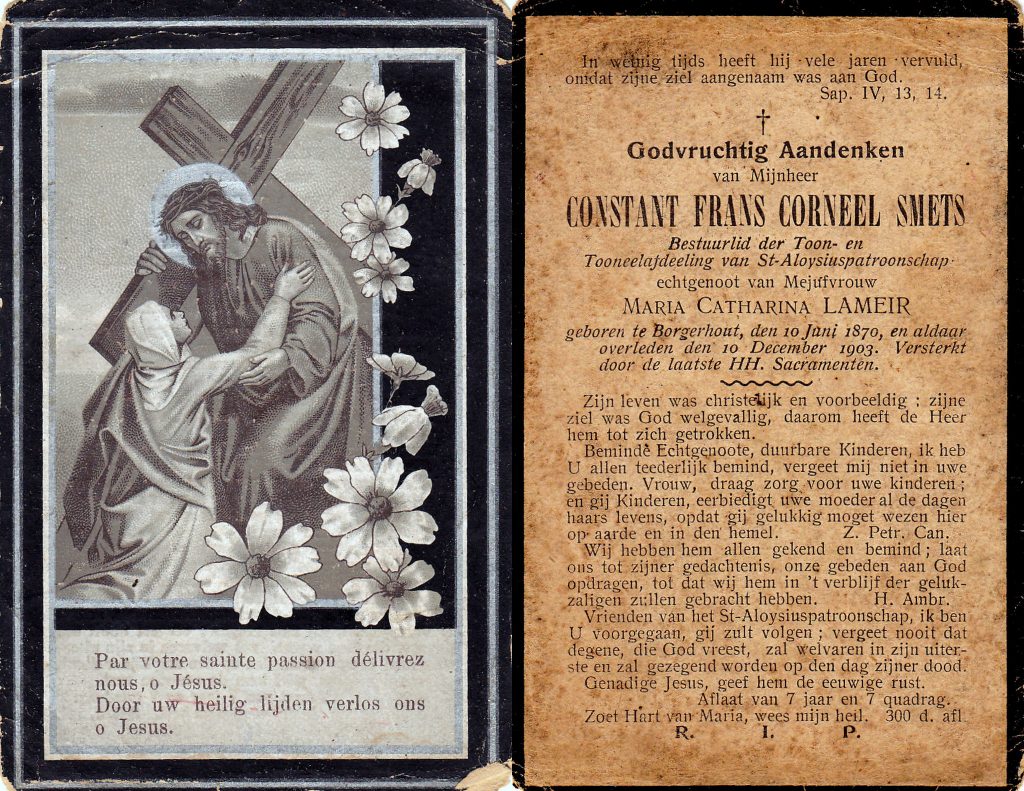

Memorial cards started out as simple devotional cards with images of the crucifixion, Ecce Homo, Mater Dolorosa, tombstones, and other memento mori on the front, and prayers on the back side. My second great-grandfather’s card, which is typical of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, features an image of Jesus crowned with thorns. The text on the reverse, framed within a black border, begins with a request to pray for his soul, and ends with an admonishment to fear the Lord, and love and comfort one another. Interspersed are several scriptural references, as well as two devotions with their respective indulgences.2

Old cards frequently allude to the deceased’s spiritual and moral character. My great-grandmother, Maria Elisabeth Wijters, a member of the Sodality of the Sacred Heart, “quietly passed through life.”

Loving and caring, she worked for her family and raised her children as model Christians. She looked for God in every deed, and found the strength of pious women and mothers in prayer, Holy Communion, and her devotion to Mary, Mother of God. She met the end of life with calmness and complete surrender to the will of God, who is the greatest solace for those who remain. This is how beautiful souls meet God. Well then, faithful and good servant, enter into the joy of the Lord.

My great-grandfather Constant Smets’s life, who died at the age of 33, was “Christian and exemplary; his soul pleased God, which is why the Lord called him.” Constant was also a member of the “Note and Theater Division” of the St. Aloysius Confraternity. No one in my family knew he had these talents until we read his memorial card more carefully!

Over the years, memorial cards have taken on a more secular character. Memberships in religious confraternities and sodalities gave way to mentions of more worldly pursuits. We discover volunteer firemen, charitable workers, musicians and actors, fishermen, pigeon fanciers, longbow shooters, billiard players, and athletes of all kind. Sometimes the cards lists the person’s occupation or mention their membership in the farmer’s or worker’s unions.

My maternal grandfather’s card mentions his childhood in a family of ten children, his work as a clockmaker, his service as volunteer paramedic and fireman, as well as his deep faith in God.

On some memorial cards we find military service citations and references to war-time experiences. Some collectors only save cards for veterans of World War I or II, prisoners of war, the deported, war invalids, or members of the resistance. A far flung cousin, Petrus Joannes Van Wesenbeeck, an infantryman during World War I, was killed on the battlefield in West Flanders.

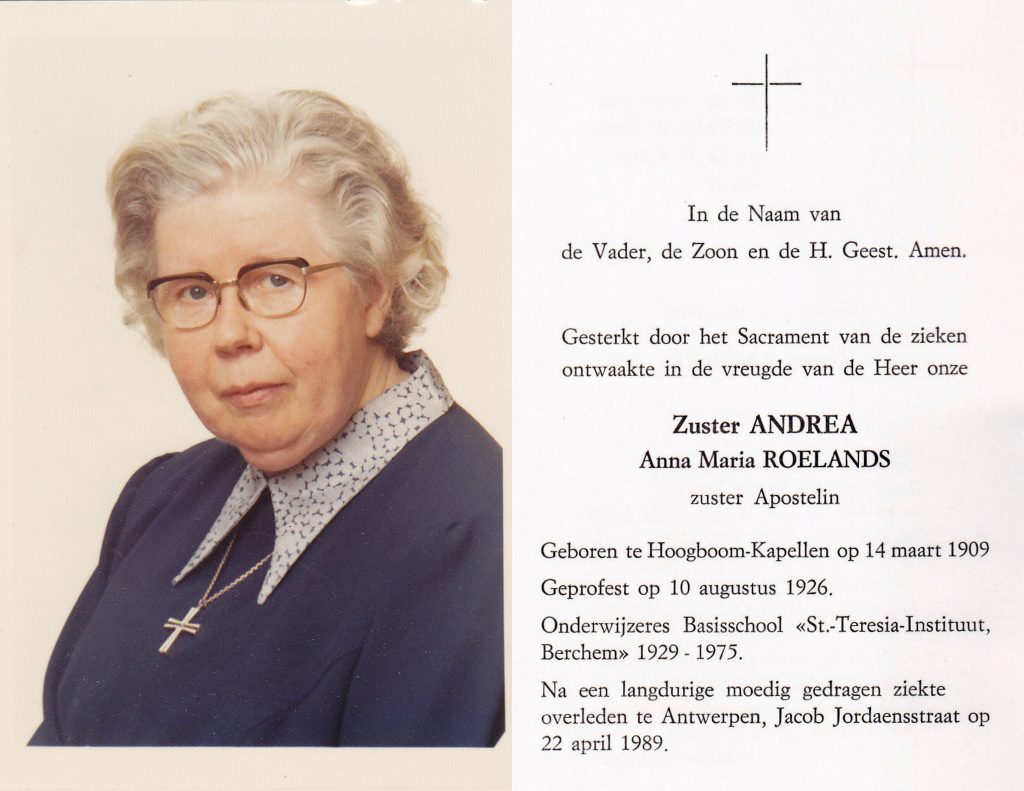

Members of the clergy and religious orders deserve mention of their novitiate, temporary and perpetual vows, ordination, religious assignments, and mission service. My tante nonneke, great-aunt Anna Maria Roelands, professed vows on 10 August 1926 with the Aposteline Nuns, and was a lower school teacher in Berchem for over 45 years. She died after a long illness on 22 April 1989.

Occasionally memorial cards hint at the cause of death, information which cannot always be found elsewhere. Death may have been suddenly or the result of a long illness. The card names a hospital, hospice, or nursing home, or references a heartrending or ill-fated accident. Subtle words may suggest death was the result of suicide.

In Belgium today, memorial cards are ubiquitous at both religious and secular memorial services. Unlike their American counterparts, they have evolved into stylish tributes to the deceased. Contemporary cards can take any shape or form. They are commonly double-sided, contain poems or favorite memories, and frequently feature a photograph. Much of the old symbolism has been lost. Crosses, rosaries, candles, doves, and other Christian symbols, while still present on some, are small and inconspicuous.9

Cite this post

Kristine Smets, “De Mortuis Nili Nisi Bene,” The Belgian American, (https://thebelgianamerican.com : accessed [date]), posted 19 February 2020.

- Also called mourning cards, funeral cards, or prayer cards. In Dutch, doodsprentje, bidprentje, herinneringsprentje; in French, memento, image pieuse; in German, Andachtsbild, Todesanzeige. For an interesting article, see Michael Williams, “Like Baseball Cards, but for Funerals,” The Atlantic, 4 February 2016; online archives (https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/02/legacy-funeral-cards/459963/ : accessed 15 February 2020).

- 2 Maccabees 12:46; James 1:12; and Apocalypse 14:13. Indulgences for certain prayers were confirmed by several popes during the nineteenth century.

- Collection of Agnes Smets, Kalmthout, Belgium.

- Collection of Agnes Smets, Kalmthout, Belgium.

- Collection of Agnes Smets, Kalmthout, Belgium.

- Author’s collection.

- Gemeentearchief Kalmthout.

- Collection Louisa Vanwesenbeeck, Kalmthout, Belgium.

- For more information on the history of death memorial cards, and to see many examples, see “Bidprentjes,” Philippe Verzamelt. To see contemporary examples, search for “rouwdrukwerk” in your favorite browser.

Wonderfully informative! Thank you again.

Thank you Ron. I am putting a list together of where you can find prayer cards and mourning letters online, so stay tuned.

Excellent article. A friend of mine in Belgium has been collecting them for many years. He has thousands of them.

I very much enjoyed reading this post. My grandparents kept all the memorial cards of their community, friends and family in a drawer in their dining room in Zwijnaarde (Groot-Gent). I used to read them as a child and be fascinated. Unfortunately my mother threw them away when my grandparents passed away. Both my parents have since passed and my sister and I spent considerable time working on their memorial cards. They are secular in nature as we are not religious and included some favorite poems and lyrics. I have shared them with my US family and explained their importance in our culture. Both cards are prominently displayed in our house and my son now reads them.

Thank you. I love that you are continuing the tradition to honor your ancestors in this way.

Thank you! This explains why my grandmother had so many in the photo box I Inherited from her. I did not realize it was cultural. This completely changes how I will approach digitizing this part of the collection.